Editor’s Note – The following blog post was originally published in an edited version on the Veteran and First Responder Healthcare blog on September 11th 2018. On this date, the 20th anniversary of the September 11th attacks and the 1st anniversary of Mission First Partners, we thought it would be fitting that our first blog post is this one in its original unedited form. The only changes are references to dates.

By John Mulet, NYPD Retired

20 years ago today, America and indeed the world as we know it changed. Prior to that day terms like sleeper cells, dirty bombs, and lone wolf attacks, were not part of the American lexicon. Then on one picture perfect fall morning, America lost its innocence, and became the victim of one of those terrorist attacks that until then we had only heard of in far-off lands. That morning and in the days following I had that rarest of all human experiences, the experience of watching history unfold before my eyes. When VFR asked me to write their 9/11 blog post, I had very mixed emotions about it, and at first decided to use an earlier post I had written but not published yet. Even after all this time it still affects me to talk about that day. But I also find that as I have talked about it, I feel like I take back some of the power it has over me. When I think back on the events of that day and the days following, so many of those days run together and are lost, yet some things are so clear in my mind they could have happened yesterday. There are so many stories I could tell. Stories about pain, tragedy, and the resilience of the human spirit. Stories that most people will never hear and otherwise would never be told. I have decided that each year on the anniversary, I will tell one of these stories. I don’t normally like talking about myself, but for this first post, the story I will tell will be my own since it will inform so many of the other ones over the years. I have not told these stories to anyone other than family and close friends over the years. But I now feel I have finally found a place where sharing them with others has a purpose. Because so many of the people reading this are dealing with traumas of their own I have omitted a lot of graphic details, but I hope my words convey a sense of what it was like to live through one of the most heartbreaking days in American history. Please forgive the length of this screed, as it will be far longer than an ordinary blog post. But there is a lot to tell.

The NYPD Emergency Services Unit raises the first flag over Ground Zero on September 11th 2001.

On September 11, 2001 I was working at the NYPD Museum at 25 Broadway right outside the statue of the bull on Wall Street. I had transferred there about six months prior from a narcotics unit in central Harlem. My wife was overjoyed when I got this transfer because she felt like I was finally someplace safe. Little did we know that we were about to find out that in many ways I was safer in a crack house on 145th St. than in downtown Manhattan. My wife and I had just moved into our first new house on the 2nd of September, and I was taking the train to work every day. I remember that day as I stepped out onto the street from the subway it was one of the most perfect fall days you could imagine. The museum was a department facility, and so it had 24 hour a day security. There was a cop from the first precinct who did the overnight security shift at the museum and as he was leaving it came over his radio that a plane had hit the World Trade Center. We went around the back of the building onto Trinity place where we could see the towers and there was no question that something had hit it, but it did not look like it was a jet. The first thing that went through my mind was the then recent crash of JFK Junior since I thought some small plane had gone off course and hit the tower. We went back inside to wait for the call from headquarters informing us of the mobilization that was unquestionably coming. I was in the bathroom when I heard a boom. The lights went off for about five or six seconds and then came back up. We ran back out to Trinity place to see the second tower had been hit, and it was badly damaged. We realized then that this was no accident. We went back inside and broke out the guns and vests since we had no idea what was happening, but we knew we were being attacked. When the first tower collapsed, I didn’t realize what was happening, but I felt the ground start to shake. My first thought was that somebody had put a bomb in the subway because the five train ran right underneath our building. I probably should’ve gotten out of the building, but instead I ran to the window. There I saw something I will never forget. Hundreds of people were running down Broadway, like something out of a 50s horror movie. Then suddenly the sky went black as night and stayed that way. After about 15 or 20 minutes the dust settled, and you could begin to see out of the window again. The Sergeant and I walked out into the street into a scene that was surreal. Dust and debris was falling like snow. Cinders were falling, but the dust itself burned your eyes, burned your nose, and burned your throat. We went back inside and turned on the TV. The news was reporting that the World Trade Center was under attack and one of the towers had already collapsed. When the second tower collapsed, we thought we were watching video of the first collapse. But then the ground started to shake again, I looked up at the TV and saw “live” in the corner. I realized the second tower had gone. There was no longer any TV being transmitted, so we only had the radio to monitor developments through the night and into the next day. I finally left the next afternoon to go home for a couple of hours, wash up, and get some clean clothes. When I stepped out into the street it was another surreal picture. All the paper from the buildings mixed with the water from the fire hoses and covered Broadway in inches of clay. There were Humvees driving down the street with soldiers and Marines on them. Helicopters flew overhead through the still hazy air. This didn’t feel like America, it felt like something out of Apocalypse Now. I got a ride to Grand Central Station from an ambulance. It was either from Pennsylvania or Ohio I don’t remember. But like so many of the emergency vehicles there that had come from all over, they were just waiting. Waiting for survivors that never came. When I got off at the train station and walked to my car there was a piece of paper under the windshield wiper. Annoyed I grabbed it wondering what could be so important that somebody had to leave a note on my car. When I opened it three lines were written on it:

I hope you made it out

God bless you

Don’t give up

I then realized it had been placed on the windshield over the NYPD parking placard that was on my dashboard. That was the first time I broke down. To this day I still wonder what happened to that note, because after that things get kind of fuzzy. Somehow, I drove home, and from what my wife tells me I took off all my clothes in the driveway, went into the house, fell into her arms, and all I said was “they’re dead, they’re all dead”. It wasn’t until later that I found out until that moment, she didn’t know if I was alive or not. After the phone lines had gone down, I got a message to her through a friend in the Bronx that I was okay, but she didn’t believe it until she actually saw me.

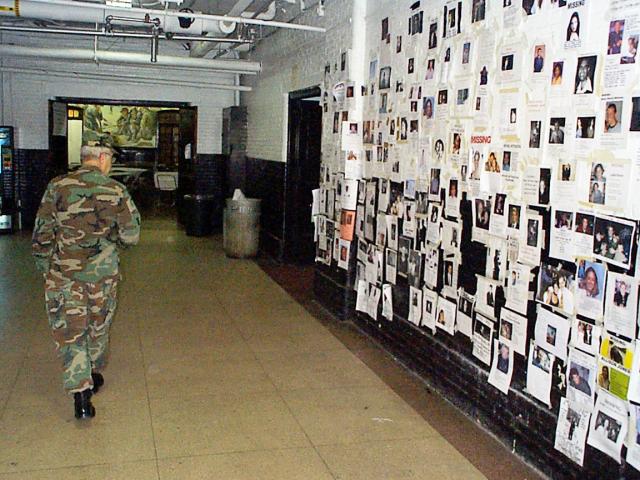

I headed back down and got stuck at Grand Central because the subways were shut down due to bomb threats. I started walking down Lexington Avenue toward downtown, and when I passed the Armory, I realized the rest of my unit was inside. It was being used as the family assistance Center. At that point there were multiple unidentified persons in local hospitals, and as they were being identified either through fingerprints, or because they had regained consciousness, it was the job of my unit to maintain the lists of names and inform family members coming in that their loved ones had been found. For days we faced lines of desperate people clinging to hope that the people they love had been found, only to have those hopes dashed by us telling them the name they hoped to see was not on the list. As a cop you understand taking away people’s freedom, you can even understand taking someone’s life, but there’s nothing like the feeling of taking away someone’s hope. Nothing prepares you for that. The Armory also gave me one of my most vivid memories of this time. The same people that were searching for their loved ones made up missing person posters and taped them on the walls of the Armory in case someone had seen them. As I looked at the pictures on them, the thing that struck me was the kind of pictures they were. Pictures from weddings, birthdays, vacations. Pictures that were probably taken on the happiest days of these people’s lives were now being used to identify them. I saw a pretty blonde woman in a wedding dress, a young man in his college cap and gown, a woman in a restaurant surrounded by friends in front of her birthday cake. 20 years later I’m still haunted by those faces.

As the effort moved from rescue to recovery, the family center was relocated to pier 94 on the west side of Manhattan and we were given a new mission. Family members were desperate to view the site, but it was blocked off to the general public. My lieutenant who had a doctorate in psychology, crafted a procedure by which three times a day we would take family members into the pit, so they could see the recovery effort. We use multiple means of support for the families, everything from therapy dogs, to Red Cross volunteers, to clergy members. It was the officers in my unit however, that were the main contacts for the families. Because of the difficulty of navigating the streets, and the desire to protect the families from the media, these three trips a day were done by ferry. We therefore became known to the other units working in the family center as “the boat people”. For three trips a day, seven days a week, for almost 2 straight months we answered people’s questions, listened to their stories, and looked at their pictures. But mostly all we could do was to comfort them while they cried, and hope they didn’t see us crying ourselves. One family I was with asked me to recite a letter they had written to their loved one with them. I’m not sure which one of us had more trouble making it to the end. As hard as the work was, I still believe it was the best work I did in my career. But, it was nothing compared to what came next.

What came next was I found what many people who go through intense trauma find. That the worst part comes when the action finally ends, and you have time to process all the things you’ve been through. I isolated myself and solitude brought out the worst in me. For a long time after, I vacillated between despair, anger, and not feeling anything, which was the worst of all. At least despair and anger make you feel like you’re still alive. That despair and anger was fed all the more by having to watch what became of my team my friends. No one emerged from this experience unscathed. There were broken marriages, broken careers, broken people. The final straw came when two years later a close friend of mine who was there with me the whole time was diagnosed with ovarian cancer at age 36. My only thought was “all we tried to do was help people, what did we ever do to deserve this”? Compounding all of this was fighting the bureaucracy of a city and a Police Department that insisted that our problems came from anything and everything except our service on 9/11. I retired in 2006, and 15 years later I am still fighting to have my injuries recognized as line of duty related, so I know well of where I speak on this. Others held their lives together with string and chewing gum, hoping to limp along to their 20th anniversary. Sadly, not all of them made it.

This is why am so grateful for the life I have today. When I speak to groups of first responders about my background, there is one thing I always tell them. I lost friends on 9/11, 20 years later I’m still losing them. I lost my career and 8 years of my life to PTSD. But maybe the only thing worse than everything I lost, are the people who were left behind and watching what became of their lives. They are the reason I do this.

Thank you all for taking the time to listen to my story, and to my fellow “Boat People” Liz, Reggie, Carla, Mike, Grace, and all the rest, wherever you are, I hope you are all well and have finally found peace. I think of you often, and miss you all.

Stay safe,

John